St. Paul - Life and Letters

St. Paul of Tarsus is the great missionary and evangelists of the early Church. Called “the apostle to the Gentiles”, Paul was relentless is bringing the good news to communities across Asis Minor and Greece. Some 13 letters of the New Testament are ascribed to his authorship. The letters are revelatory about life in the early Church and the basic kergyma of faith – that essential proclamation of Christ as Lord and Savior. This lesson plan is but an introduction to the life and letters of St. Paul.

-

Early LifeSt. Paul

-

ConversionSt. Paul

-

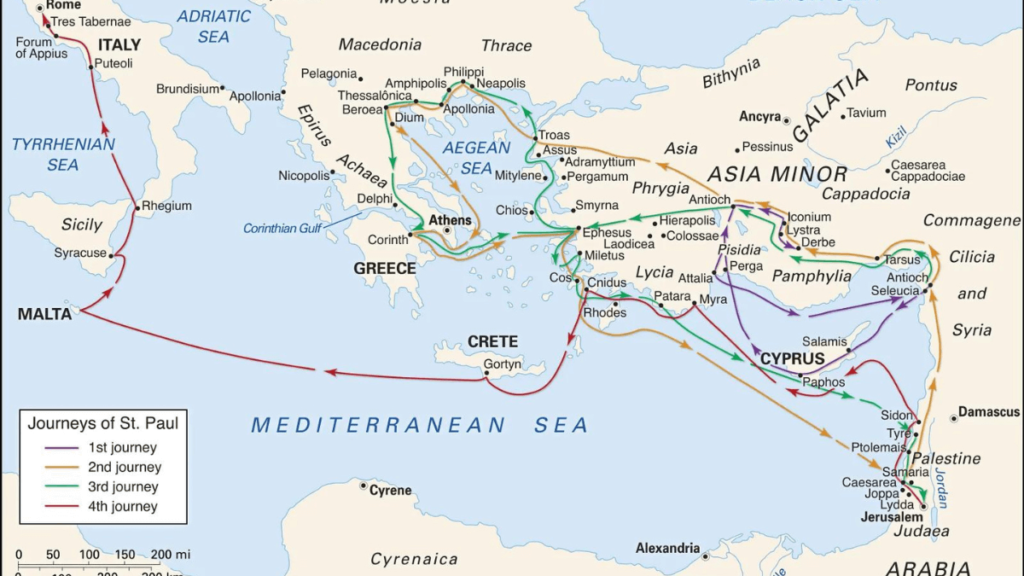

Missionary ActivitiesSt. Paul

-

Lesson 4Romans

-

Lesson 51 Corinthians

-

Lesson 62 Corinthians

-

Lesson 7Galatians

-

Lesson 8Ephesians

-

Lesson 9Philippians

-

Lesson 10Colossians

-

Lesson 111 Thessalonians

-

Lesson 122 Thessalonians

-

Lesson 131 Timothy

-

Lesson 142 Timothy

-

Lesson 15Titus

-

Lesson 16Philemon

Early Life

Often, we first encounter Paul in The Acts of the Apostles, which includes biographical material about him as captured by either a travel companion or someone who collected the travel stories. But we also have thirteen Letters in the NT that are ascribed to Paul that serve as a more primary source of biographical information. Still, as best we can, we use the sources available to stitch together a “biography” of this great missionary saint.

According to Acts (21:39; 22:3), Paul was born and reared a Jew in Tarsus, an important city of Cilicia. The date of his birth is uncertain but is usually estimated at about a.d. 10. In a statement reported in Acts 22:28, Paul claimed that he had been born a Roman citizen (see 21:39). This would mean that he had inherited citizenship from his father (or some other ancestor) who had done meritorious service for the Romans. Paul’s use of Greek confirms his origin as a Hellenistic Jew of the Dispersion, at home in the Greco-Roman world.

Paul’s earliest education would have been in the home, with his father as instructor. The loyalty of Paul’s parentage to the ancestral faith remains a mark of pride. Of himself Paul boasts, ‘circumcised on the eighth day, of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews’ (Phil. 3:5). At about age six, Paul would have attended the synagogue school for instruction in the Scriptures and Hebrew. Paul, according to Acts 22:3, was educated in Jerusalem ‘at the feet of Gamaliel.’ This teacher would have been the important Rabban Gamaliel, noted for his spirit of tolerance (Acts 5:34–39). Although his Letters never mention a rabbinic teacher, Paul’s arguments reflect methods of biblical interpretation used by the rabbis. Paul, like most rabbis, was a member of the Pharisaic party (Phil. 3:5).

Early in life, Paul learned a trade, probably from his father. The trade was tentmaking and other leatherwork (Acts 18:3). Practice of this trade provided Paul later with means to support his missionary activity (1 Thess. 2:9; 1 Cor. 9:6).

Prior to his conversion, Paul had been a persecutor of Christians. Acts reports that he ‘laid waste the church’ and ‘dragged off men and women and committed them to prison’ (8:3). He ‘persecuted them even to foreign cities’ (26:11), receiving authority from the high priest to extradite Christians from Damascus (9:1–2; 22:5). What jurisdiction the Jerusalem hierarchy might have had over inhabitants of distant cities is problematic, and Paul’s assertion that he was ‘still not known by sight to the churches of Christ in Judea’ (Gal. 1:22) raises questions about his persecuting activity in Jerusalem. That Paul had been a persecutor, however, is confirmed by his Letters: ‘I persecuted the church of God violently and tried to destroy it’ (Gal. 1:13; see Gal. 1:23; 1 Cor. 15:9). As a Pharisee, Paul may have been angered by the failure of the followers of Jesus to live strictly by the requirements of the law (see Gal. 1:14). He was no doubt enraged by the Christian identification of the crucified Jesus as Messiah (Christ). Paul had expected a triumphant messiah, not one who bore the curse of the cross (Gal. 3:13). For Paul, the crucified Christ had been a stumbling block (1 Cor. 1:23).

The late-second-century apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla describes the apostle as ‘a man small of stature, with bald head and crooked legs … with eyebrows meeting and nose somewhat hooked.’ Paul himself reports that his critics say ‘his bodily presence is weak, and his speech of no account’ (2 Cor. 10:10). Paul’s physical weakness is epitomized by his ‘thorn in the flesh’ (2 Cor. 12:7). The report of the thorn, together with references from Galatians (4:13, 15; 6:11), has been variously interpreted to imply that Paul was afflicted by such disorders as malaria, eye trouble, or migraine headaches. In spite of this unidentifiable malady, Paul had the strength to overcome serious physical obstacles (2 Cor. 11:24–28). Paul was a person of strong emotional expression: once a persecutor of Christians, later a bitter foe of opponents (Gal. 5:12; 2 Cor. 11:13).

Conversion of St. Paul

Paul’s conversion was not without preparation. As a Jew influenced by speculation about the future, Paul had looked forward to the coming of the Messiah. As a persecutor, Paul had heard the message of the disciples and had been impressed by their perseverance. His conversion did not involve turning to a new God (see 1 Thess. 1:9); before and after, Paul worshiped the God of the Old Testament (OT). Moreover, Paul’s conversion did not involve a serious moral trauma. Paul claimed that, before he accepted Jesus as Christ, ‘as to righteousness under the law’ he had been ‘blameless’ (Phil. 3:6).

Paul’s conversion is presented in the form of a call narrative, like that of the prophets (see Jer. 1:4–10). This is clear from his most extensive account (Gal. 1:11–17), where the experience is seen to involve two main elements: the revelation of Jesus as God’s Son and the commission to preach him to the Gentiles. In Acts, the conversion of Paul is recounted three times (9:1–19; 22:3–16; 26:4–18). These accounts stress supernatural details: light and voices from heaven, Paul’s blindness and recovery. They also observe that Paul’s conversion was facilitated by a religious leader (9:10–18; 22:12–16) and that Paul was baptized (9:18; 22:16)—events nowhere mentioned in Paul’s Letters. For Paul, one feature was crucial: he had seen the Lord (1 Cor. 9:1); the risen Christ had appeared to him (1 Cor. 15:8). This vision led to the conviction that the crucified Jesus was the Messiah. It also showed that the events of the end of history had started to unfold and that, in these last days, God was accomplishing his divine purpose through the crucified Christ, as power working in weakness (2 Cor. 12:9).

Paul’s conversion is presented in the form of a call narrative, like that of the prophets (see Jer. 1:4–10). This is clear from his most extensive account (Gal. 1:11–17), where the experience is seen to involve two main elements: the revelation of Jesus as God’s Son and the commission to preach him to the Gentiles. In Acts, the conversion of Paul is recounted three times (9:1–19; 22:3–16; 26:4–18). These accounts stress supernatural details: light and voices from heaven, Paul’s blindness and recovery. They also observe that Paul’s conversion was facilitated by a religious leader (9:10–18; 22:12–16) and that Paul was baptized (9:18; 22:16)—events nowhere mentioned in Paul’s Letters. For Paul, one feature was crucial: he had seen the Lord (1 Cor. 9:1); the risen Christ had appeared to him (1 Cor. 15:8). This vision led to the conviction that the crucified Jesus was the Messiah. It also showed that the events of the end of history had started to unfold and that, in these last days, God was accomplishing his divine purpose through the crucified Christ, as power working in weakness (2 Cor. 12:9).

Missionary Activities of St. Paul

Paul’s missionary activities are detailed in The Acts of the Apostles and the various Letters written during those missionary years. There is some debate about the timeline between the Damascus Road experience and the first missionary endeavors descried in Acts, but as best we can know, after his conversion in about a.d. 34 or 35, Paul spent three years in Arabia (Gal. 1:17) likely to refocus his Jewish roots with the promise of Christ. His first visit to Jerusalem after his conversion occurred around 37. Although the account in Acts presents him as ‘preaching boldly’ (9:29), Paul’s own testimony is that he saw only Cephas and James (Gal. 1:18–20).

From this point on until his death, probably in a.d. 62, Paul tirelessly evangelized across the Mediterranean basin – some 25 years of missionary work.

The Letter to the Romans

Paul did not establish the Roman church as he had others. It was established by members of the Jewish-Christian community in Jerusalem who had traveled to Rome. But about a.d. 49 Emperor Claudius ordered the Jews expelled. After Claudius died around year 54, Jewish Christians who returned to Rome were surprised to meet a large number of Gentile Christians. Converts had multiplied. The Roman Christian church, then, to whom Paul sent this letter was predominantly Gentile-Christian.

Paul had not visited the Roman church and so in one way this Letter to the Romans serves as an introduction. The letter was likely written from the city of Corinth to the Christians in Rome. The date is probably very late in a.d. 56, or early in 58, during the winter. As part of his missionary endeavor, Paul encouraged the various Gentile churches he had founded to take up a collection which he would personally deliver to the poor in Jerusalem (Rom 15:25–27). His plan was to visit Jerusalem briefly and then to set out for Spain and the West with an intervening visit to Rome (15:28).

In addition to introducing himself to a community which for the most part did not know him personally, Paul could marshal, evaluate, and summarize the arguments he might have to present in Jerusalem if his preaching were still being challenged. In this way Romans is an opus magnum. Scholars offer other possible reasons, but those are the stuff of speculation. History shows that Paul was arrested in Jerusalem, imprisoned in Caesarea for two years, and finally arrived in Rome around a.d. 60 or 61, some three or four years after his letter had arrived.

If you would like to read more details about this letter, the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Romans

There are many suggested outlines for Romans, here is but one:

GREETINGS AND INTRODUCTION (1:1-17)

SUMMARY OF PAUL’S GOSPEL (1:18–11:36)

- The Human Condition Without Christ (1:18–3:20)

- Salvation Through Faith in Christ (3:21–4:25)

- The Christian Life (5:1–8:39)

- Israel’s Hope (9:1–11:36)

EXHORTATION TO HARMONIOUS LIVING (12:1-15:13)

- Conclusion (15:14–33)

- Phoebe Commended (16:1-23)

- Concluding Doxology (16:25-27)

The First Letter to the Corinthians

At the time Paul wrote these letters (about 56–58 c.e.), Corinth was probably the leading Greek city, its rival, Athens, having declined in political and economic importance. Corinth was a port city with merchants and vessels arriving from and leaving for other ports-of-call. The town exhibiting all the tough features of an important city of commerce whose population was mixed and mobile. Corinth had all the best and the worst of a vital, throbbing pagan capital. The high ideals of Greek civilization challenged citizens of Corinth to a certain spirituality, asceticism, and cultivation of the aesthetic. The worst in pagan vices was nourished by the Greeks’ scorn of the physical, a scorn that had given birth to such apparent opposite extremes as hedonism and stoicism. Economic and political growth did not necessarily promote ethical development. The Corinthians’ reputation for licentiousness was well known. Religious syncretism provided the melting pot for Jewish, Roman, and Greek practices that tended to boil down the precious and leave a residue of counterfeit alloys.

In other places, Paul was an itinerant preacher, but he set down “roots” in Corinth staying, working and preaching for 18 months. According to Luke, Paul first tried to evangelize the Jewish population, enjoying a modicum of success (Acts 18:1–4). After continued problems with that segment of the community (Acts 18:5–6, 12–17), Paul reviewed his priorities and focused on the Gentile community.

This first letter to Corinthians deals with divisions, zealous Gentile converts who lack maturity and depth, a community whose practices did not always line up with their professed faith. The letters also point to a lingering dualistic thinking among the Gentile converts that tended to separate the body and the spirit, claiming superiority for the latter while neglecting the physical. This led to misunderstandings about Christian marriage, dietary practices, taboos, and even resurrection.

The Letters to the Corinthians are not theological dissertations, they are pastoral letters to troubled community, written by their shepherd working to keep the flock together and following Christ.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: First Corinthians.

The Second Letter to the Corinthians

Nowhere else in Paul’s writings is the passionate human character of this great apostle more evident than in Second Corinthians. Here we have the personal testimony of Paul, his ardent reactions when distrusted and accused and concerned about a community he loves deeply. There in broad strokes Paul paints his own profile and, at the same time, gives us a look inside himself, at his vulnerability and strong feelings for others. Second Corinthians conjures up that part of Paul which most attracts us — his depth, his affection. Second Corinthians also provides the focus on what readers most dislike and suspect in Paul and what they are most likely to misunderstand and reject.

In a sense, this appears as a very harsh letter, punctuated with solemnity and oaths, issuing corrections and warnings spotted with threats of severity, self-justification, and complaints. The Corinthians, for their part, seem to be incorrigible in their need to measure and control love as they demand proof that they are loved by the Apostle. Paul counters their skepticism and competitiveness with reminders about the only evidence admissible to the only court he recognizes as valid. Before God and before the tribunal of Christ, the faith of the Corinthians provides the irrefutable witness of the Apostle’s authority and integrity.

In Second Corinthians Paul stresses the value of suffering as a witness to the truth of the gospel. So powerful is this witness that suffering is transformed from an evil into the most eloquent testimony of faith. In First Corinthians, Paul presented the cross as the decisive truth, folly for those who were perishing, but salvation to those with faith. In Second Corinthians, Paul describes his own suffering as indisputable evidence of his call as an apostle, of his authority to make all things subject to God in Christ, of his mission to share the ministry of reconciliation with others. An experience of suffering and of receiving God’s healing mercy qualifies the minister of the new covenant.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Second Corinthians.

The Letter to the Galatians

Unlike the letters to the community of Corinth, we are not exactly sure to which specific community this letter is addressed. Initially, the name Galatia described a north central section of Asia Minor which contained the cities of Ancyra (modern name Ankara, Turkey), Pessinus, and Tavium. Rome combined this section with southern territories into one province named Galatia, though these latter territories preferred to keep their names. It is not clear for whom the letter is intended nor exactly when it was written, although the range is thought between 49 and 55 AD.

The letter itself makes clear that the recipients of the letter are converts to Christianity from paganism, but it also evident that not too long after he departed Judaizing Christians came along and argued that in order to be a good Christian one had first to be a good Jew by being circumcised and by observing other prescriptions of the Torah. This, of course, struck at the heart of Paul’s conviction that the Torah was no longer binding as law, but continued to be Scripture, that is, story telling how Israel arrived at its present situation. News of the wavering faith of his converts prompted Paul to write this very polemic letter.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Galatians.

The Letter to the Ephesians

Ephesians offers a portrayal of the cosmic Christ (as does Colossians), but Ephesians is unique among New Testament writings for its description of the church as one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. It is this teaching on the nature of the church that is the key contribution of Ephesians.

Ephesians also emphasizes the unity in the church of Christ that has come about for both Jews and Gentiles within God’s household. The unity is achieved in a seven-fold fashion: church, Spirit, hope; one Lord, faith, and baptism; and the one God. In the light of the subsequent history of the church, it is significant that the author of Ephesians saw no conflict between the existence of an institutional church and the work of the Holy Spirit. In fact, the Spirit is mentioned more frequently in Ephesians than in many other writings within the Pauline tradition

While the letter is addressed to the Ephesians among whom he lived and worked for two years, it lacks a greeting or even a personal tone. Some scholars think this is a “circular letter” written to a church community that was expected to copy it and send it along to the next community – perhaps on the old Roman postal route.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Ephesians.

The Letter to the Philippians

Philippi, in northeastern Greece, was a city of some importance in the Roman province of Macedonia, named after Philip, the father of Alexander the Greek.

The letter shows Paul at his pastoral best — at one moment he is praising the community, then teaching, then encouraging, then admonishing, then warning, but always clearly loving the members of this community as he gives it advice and direction. He speaks to this community of Philippians with the pride of a founding father and frequently associates the words “joy” and “rejoicing” with it. Yet, there is a complex set of circumstances in which the community is living. On one hand it is struggling against hostile neighbors, and on the other it is troubled by visiting missionaries who, in one case, say things differently than Paul does, but still preach the gospel and yet, in another case, directly contradict Paul’s presentation of the Christian message.

Although the Letter to the Philippians looks like one document, a closer inspection of the text shows that it is likely three originally separate letters of Paul have been welded together to form our present text. While we cannot be sure why this was done, it may simply have been a more adequate means of preserving these apostolic writings, especially when they were passed on to other Christian communities for their edification.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Philippians.

The Letter to the Colossians

Colossae, a small town in the southwestern area of modern Turkey near the neighboring towns of Laodicea and Hierapolis, had not been visited by Paul, but he had apparently heard of issues present in the community by teachers who by placed an exaggerated emphasis on Christ’s relation to the universe with a stress on cosmic features such as “principalities and powers”, angels, astral powers and cultic practices and rules about food and drink and ascetical disciplines. Paul presents Christ as preeminent above all.

Paul’s letter reminds and refocuses the community’s attention to the redemptive power of Christ whose death and resurrection was the portal for salvation. One comes in touch with the power through the waters of baptism and leads one on the path of true ascetical practice of love – the ideal of the true Christian life.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Colossians.

The First Letter to the Thessalonians

Acts 16-17 describes Paul’s missionary foray into Asia Minor, one stop of which was Thessalonica which was only for a short period of weeks (three sabbaths) when the Jewish leadership brought Paul and Silas before the local magistrate. They posted bond (surety payment) and moved on to Borea while leaving Timothy behind. Some many months later Timothy reports to Paul the state of things in Thessalonica, and this is the occasion of the first letter.

The community is focused on the saving event of the “day of the Lord” at the end of time. Paul encourages them to have confidence as the day of the Lord approaches and that they should go about their everyday lives in a calm, responsible, and loving manner. This is advice valid for all times, and in this regard, Paul points out the importance of Christian example. How one lives one’s Christian life affects others, Christians and non-Christians alike. For Christians, it is a means of strengthening one another in faith and in our common commitment to serving God as we await that final glory promised to us. For non-Christians, our example bears witness to the radicality of our commitment to a God who wills that we live as God’s children, that we owe allegiance to something beyond ourselves which is one, true, and living.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Thessalonians.

The Second Letter to the Thessalonians

Second Thessalonians is a pastoral letter which addresses a number of problems that have arisen in a Christian community jolted by the claim that the “day of the Lord” has come upon them. Some in this community have reacted in terror, quit work, and are making a general nuisance of themselves to others within the community as they await the full effect of the Lord’s coming.

Paulseeks first of all to comfort the agitated and disturbed with the message that the day of the Lord is not yet here, for certain events have to take place yet before that happens. Meanwhile, the community is to continue going about its everyday existence as usual, calmly exercising its Christian responsibilities and earning its own keep. Paul is concerned that the faith itself, as well as individual members of the community, may come into disrepute and disbelief if fanatical doomsday preachers are listened to.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Thessalonians.

The First Letter Timothy

In many ways this letter seems to be extended codes of “household duties,” a common form of exhortation in pagan, Jewish, and Christian literature. The letter establishes very traditional moral materials, echoing not only gospel sources but Pauline advice to his churches and Petrine materials as well. Most importantly, we find a formal written document which certifies the present status of Timothy as church leader and which subsequently authenticates his successors. These letters, then, stress church order and morality and so function as official constitutions for their respective churches. no longer does Jesus commission apostles, nor is leadership designated by God’s Spirit, but volunteers arise and are validated by the church

Together with 2 Timothy and Titus, these letters form the “pastoral letters,” differing from the others in form and contents. All three suggest they were written late in Paul’s career where the “opponent” is no longer synagogue leaders but local gnostic cults. But in the main, the letters are instructions to working pastors in maintaining gospel authenticity in the light of a growing community in need of organization and leadership.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Letters to Timothy.

The Second Letter Timothy

This letter, like the preceding one, urges Timothy to protect the community from the inevitable impact of false teaching without fear of the personal attacks that may result. It recommends that he rely on the power of the scriptures, on proclamation of the word, and on sound doctrine without being troubled by those who do not accept him. The letter poignantly observes in passing that Paul has need of his reading materials and his cloak and, what will be best of all, a visit from Timothy.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Letters to Timothy.

The Letter to Titus

Like the pastoral letters of 1 and 2 Timothy, the letter to Titus is addressed to a person in charge of a growing and developing church community. Titus was with Paul and Barnabas on the first mission, but now ministers in Crete, a place Paul had never visited. It is clear that the church has taken on offices with roles and duties – Paul outlines the characteristics of those serving in the positions. Paul also describes Christian behavior for all in the community as a matter of living witness of the grace of God.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Letters to Titus.

The Letter to Philemon

The short letter to Philemon is addressed to one individual dealing with the circumstances of a run-away slave. With this letter Paul is asking that the slave be welcomed willingly by his old master not just as a slave but as a brother in Christ. Paul’s letter neither condones or condemns the institution of slavery, but focuses on establishing a new relationship because of the love of Christ.

If you would like to read more details about this letter the US Catholic Conference of Bishops (USCCB) has a general introduction that considers more technical details. You can find the introduction here: Letters to Philemon.