A Time of Doubt

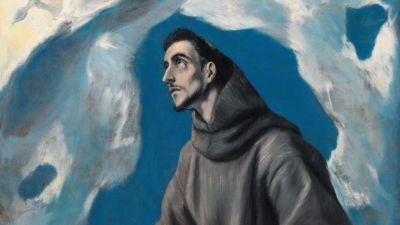

St. Francis of Assisi

Francis took the “fork in the road” that left him free of leadership responsibilities for the Order. But as things changed/evolved, Francis began to wonder if he’d chosen the right direction.

In the short span of 12 years (1209-1221), the Franciscans had grown from a small, Assisi-based fraternity consisting of Francis and four other brothers, to a large, “multi-national,” religious order with an approved Rule of Life, a Cardinal Protector (who would soon become Pope), and more than 5,000 brothers. There was nothing in Francis’ life that prepared him for leadership of such a far-flung fraternity, which was already spanning the European continent and parts of the Middle East and North Africa. He had been a spoiled dilatant, a would-be knight, a wounded warrior, a solitary figure, living a quasi-hermetical life, and now he was the “leader” of a growing, international community of brothers. In the beginning, things just seemed to unfold, signs appeared along the way, and Francis followed the path in faith. And people followed Francis. Now most Franciscans had never met Francis and Francis’ model of leadership by example, which worked in 1209, but was not the one needed in 1221. And so he stepped down as leader, leaving the Order in the care of the Church – at least as far as discipline and administration. Yet it was also clear that he hoped to preserve a superior authority, of a spiritual type, demonstrated in the way in which he lived the Rule of Life.

The scholar André Vauche refers to the years following his relinquishing of leadership as the “Time of Doubt.” It was a time in which everything in and around the Order was changing and all at once. It naturally led Francis to wonder what the future held for him and what would happen to the Order. The seeds of his doubt can be found in some fundamental changes. The life of the friars was attracting men who were already ordained as priests. The ordained brothers were educated and sometimes scholarly men, while the non-ordained brothers were tradesmen and often unlettered. Despite the ideal of fraternal equality, a natural distinction began to form. At the same time, as the needs of the Church grew in response to the mass movement of feudal peasants to the cities, the friars were requested to move to the cities to minister to the poor, homeless, and destitute – and to provide pastoral and sacramental support for these people. There was a natural movement toward ordained ministry as a means of service. It was simply an evolution within the Order in response to the needs of the Church.

But simple evolutionary changes have unintended consequences. If there is a need to form priests, then there is a need to have houses of formation and study, to possess books, and all manner of property. These were new and emerging needs for a Religious Order whose Rule of Life did not permit the ownership of property. And it was not just in the formation of priests. When the Order began doing more and more “urban ministry,” the friars began to live in the “convento” (friary) and the once-wandering friars began to stay in one place. The wild, open-road prayer life of Francis began to be tamed in the regular prayer of the breviary. Both forms of prayer are good, but it still represented a sea of change that left the original band of brothers wondering and the new brothers ready to forge ahead. Francis began to have doubts whether the fundamental ideals of evangelical simplicity and itinerancy were threatened.

There is evidence of a growing milieu among the brothers that pointed to an excessive infatuation with books, scholarly work and intellectual pursuits. At a time when books were expensive, the need and desire for them was moving the fraternity towards the patrons who could afford the books and away from the poor. Apprehensive that the brothers’ desire for books was symptomatic of a larger trend away from evangelical poverty and simplicity, Francis declared: “If my brothers had listened to me, no one would have possessed anything other than the habit allowed by the rule with a cord and britches.” (Assisi Compilation, AC 101) And to a novice who wanted to have a psalter with him, Francis sharply answered:

“When you will have a psalter, you will want a breviary; and when you will have a breviary, you will install yourself in a throne like a great prelate, and you will command your brother: ‘Bring me my breviary!’” Carried away by passion, he took some ashes from a hearth, sprinkled them over his head and rubbed them in, all while repeating, “I’m a breviary, I’m a breviary.” (AC 104)

Yet a part of Francis knew the evolutionary movement was inevitable. This is what one senses in a response to St. Anthony of Padua who had asked for permission to teach theology to the brothers in his friary. Francis’ letter is both positive and reserved. “Brother Francis sends greetings to Brother Anthony, my bishop. I am pleased that you teach sacred theology to the brothers, providing that, as is contained in the Rule, you ‘do not extinguish the Spirit of prayer and devotion’ during study of this kind.” (A Letter to Brother Anthony of Padua). Francis was not an enemy of learning nor was he unlettered. Several times in earlier writings he expressed an esteem for theologians who made the Word of God easier to understand.

In 1217, Francis had sent missionaries throughout Europe and into the East as wandering apostles who stayed in precarious shelters, begged for good, preached repentance, and gave witness to the humble and poor Christ. The Franciscan missionaries to Germany and England were quickly accepted and offered living spaces, chapels, and even offers of newly built cloisters. Everywhere about Francis were signs that those who had once been moving to the ends of the earth for Christ were tempted, ordered, or desirous of settling down.

Francis faced an uncertain future in his own vocation, in the life of the Order he had founded, and was beset by nagging health issues from his travels in the Middle East. He was a man of faith increasingly plagued by doubts.